Allan Cain

Ship name / Flight number: BA 888

Arrival Date: 31/03/1977

b. 29/09/1957

I was born in Mato Gosso, Brazil, 300-400km west of San Paulo. My father was born in Argentina, but his father was born in Surrey. My father returned to England during World War II to assist with the war effort and joined the RAF (Royal Air Force). He met my mother in England but when the war ended, he was repatriated back to South America. He didn’t want to return to Argentina because his parents had moved to Rio de Janeiro in the south-eastern region of Brazil. They also had a property in Mato Grosso, so he went to work there as an accountant.

I spent the first seven years of my life growing up in the central western region of Brazil, speaking Portuguese and playing with my three siblings. We moved to the UK in 1964 because my mother developed breast cancer and her family insisted that she come back and get treatment. My parents spent all their savings on an operation for my mother in Brazil and didn’t have any money left over to establish themselves in the UK.

Unfortunately, it was one of the worst times to migrate to the UK as the unemployment rate was high and there was a housing shortage. It was also freezing, especially in our short-sleeved shirts and sandals.

Wood inlay table made by Allan in 1970.

I went to school for the first time and sat there like a vegetable because I didn’t understand a word of what was being said. My peers were also a couple of years ahead of me in their learning because you start school when you are about five years old in the UK. There were no English lessons. The other students couldn’t understand how I could look like them but not speak English. I was teased and bullied and felt isolated. I was anxious and scared at school and started wetting the bed and biting my nails. My teachers thought I was stupid and recommended a boarding school in Colchester, which was a special school. The students in this school were developmentally delayed but at least there was no more teasing (and the bed-wetting stopped).

During the five years I was at the special school, I was able to learn English. Charlie Dollar, a teacher who was the spitting image of American Actor Clark Gable, taught me woodworking and took me fishing. By the time I left that school, I had the equivalent of a year 1 education.

I had to go to a ‘normal’ school again for high school, but all the lessons went over my head. Eventually I lost interest in studying. The only class I enjoyed, and excelled at, was woodworking. I still have the timber inlay table that I made when I was 13 years old. (My parents brought it with them when they migrated to Australia.)

‘Brookwind’, the boat that Allan purchased in 1977 and started to renovate.

I left school at the age of 15 and walked the streets looking for a job. A local nursery gave me a job that no one else wanted to do. I was told to hoe an acre of ground that was covered with stinging nettles and pull up and transplant the wallflowers. It took patience and determination over two weeks, but the boss was impressed that I had passed his test and offered me more work. I stayed there until I had enough money at the age of 17 to buy a motorboat in Norfolk.

‘Brookwind’ was a 40-foot, 13.5 tonne boat made of Burma teak and mahogany and was built in 1922. I bought it from George Smith and Sons boat yard. It came about because one day I hired a boat with a friend to take a cruise around the Norfolk Broads and thought it was really peaceful and beautiful. I said that I’d like to be able to buy a boat one day and the owner of George Smith and Sons boat yard, who assumed that I was a landscaper because I worked at a nursery, offered to sell me one if I paid a deposit and landscaped his extensive front yard for free. He paid for all the materials, and I spent three months working in Norfolk to get my boat. Given the amount of financial hardship in the UK in the mid-1970s, I felt this was an accomplishment.

I put my boat in a dry dock and started to renovate it, until I was called up for an interview in London at Australia House.

I came to Australia because of a film. One afternoon, it was pouring with rain (as it often is in England) and a film came on the TV called ‘The Sundowners’. After watching it, I told my dad that I’d like to go to Australia. I wanted the sunshine and wide-open spaces on the film set. About three weeks later, there was an advertisement in the newspaper from Australia House which said: “Australia wants migrants”. I asked my dad what a migrant was and realised that this was me.

The poster advertising ‘the Sundowners’ movie.

Allan Cain’s passport photo, 1976.

Allan after his haircut, which the BBM insisted he get before he immigrated.

I nagged him to write to Australia House for me (I couldn’t write well enough) and fill in the application form. I was called up for an interview, but it didn’t go particularly well. I didn’t have any qualifications or anything to offer Australia. Luckily, a man who had worked for the BBM for many years, Mr Samson, was present at my interview, even though he was riddled with arthritis and in a wheelchair. He said that the BBM was founded for boys like me and insisted that I be allowed to go.

I was given a list of things I had to take. I turned up at Heathrow airport in March 1977 wearing my suit and with my long hair cut off. I looked more professional than my well-educated fellow travellers who had ignored the requirement to wear a suit, so I was given the paperwork to look after on our trip to Sydney.

When we finally got to Sydney, we had to circle the airport several times waiting for an opportunity to land. I kept looking out the window expecting to see an outback, sunburnt landscape, but it looked like a sophisticated and upmarket city. I was petrified. I didn’t feel that my limited education had prepared me for living in a big city and I was afraid that I’d made a terrible mistake. Luckily, I connected with an Irish Little Brother who kept me company when we moved to the hostel in Burwood. His companionship was reassuring.

The BBM really wanted me to stay in Sydney, but I was scared and refused. I said that I wanted to ‘go bush’. I caught the train to Trangie (past Dubbo) and went to ‘Auburn Farm’. It was run by a German family by the name of Heckendorf. My living quarters were an old donga type shed, which had more holes in the roof than you could poke a stick at. My mattress was a pile of newspapers on a metal frame, and my blanket was more newspapers. It was freezing cold, especially at night. They gave me a blanket full of holes and then deducted this from my pay of $25/week.

The Heckendorf family were Seventh Day Adventists and went to church in Narromine each Saturday. After a couple of weeks, I asked if I could get a lift into Trangie on their way to church. They agreed, so I went into town and bought my first Akubra hat. Now I was starting to look like a character from ‘The Sundowners’! I was looking for somewhere to buy batteries for my radio and walked into a little electrical store. This is how I met Peter and Jean Foster. Peter came through the BBM 30 years prior to me.

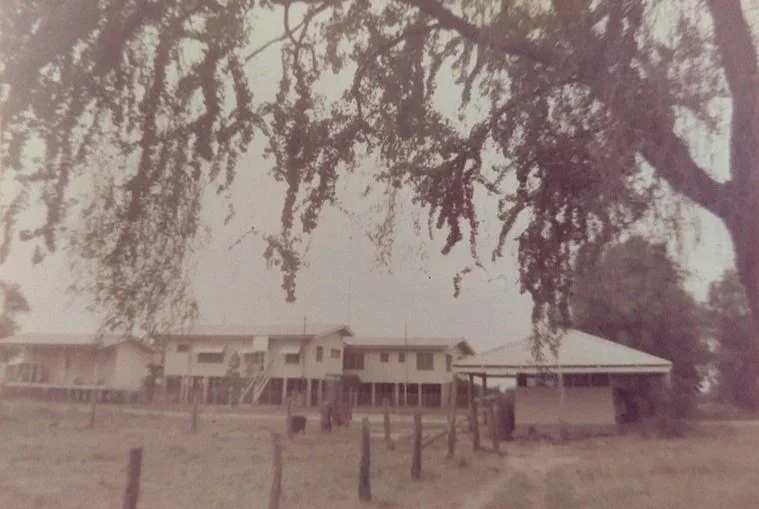

The homestead at Auburn farm, which was run by the Heckendorf family, Trangie, 1977.

Jean Foster (seated, 2nd from left) and Peter Foster (wearing glasses), 1978.

‘Ellengerah Station’, Trangie, 1977.

When I told him that I was working for Heckendorf he said: “no you’re not. We are going to get you another job”. Peter helped me to get a job at ‘Ellengerah’, which was the best place ever. It was about 17,000 acres of mixed farming: sheep, cattle, sorghum, lucerne, and wheat. It belonged to the Stanbroke Pastoral Company, and the manager was Ian Knight. Ian taught me how to drive tractors, shear and crutch sheep, muster cattle, build fences – anything and everything.

My first experience of riding a horse at ‘Ellengerah’ did not go well. When I went to the yard to get a horse, the ‘old hands’ said they would catch one for me and saddle it up. However, they wanted a bit of fun (at my expense) so they left the girth loose. As soon as I threw my leg over the horse, the saddle swung around, and I found myself under the horse’s belly. Naturally, the horse was scared and took off. I was lucky not to be killed.

On the weekends, the other stockmen used to go into Trangie to drink. My father and grandfather didn’t drink, and I decided not to as well. Instead of going to the Trangie pub, I used the time to teach myself how to catch and mount a horse. Come Monday, my horse came walking over to me in the yard and bowed its head so I could slip the harness on. It would also wait for me when I dismounted. The other stockmen were amazed that I had become so competent so quickly.

Shearer’s quarters at Ellengerah Station, 1977.

Macquarie River, which flowed through ‘Ellengerah’ station and where Allan rained his horse, 1977.

Ian Knight noticed that I was a quick learner so when he had to go to Melbourne to progress the sale of ‘Ellengerah’, he left me in charge of the station. The head stockman who had been there for years was mightily offended by this and took off in a huff with his swag in his ute. I did more than Ian required and improved the property so much that he didn’t recognise it – he drove past the front gate when he came back from Melbourne. Because it was summer and the days were longer, I did lots of extra work in my own time, such as clearing weeds, slashing the long grass and painting and re-installing the entrance signs. Ian rewarded me with a $4000 bonus. I used the cash to buy my first car: a 1974 Falcon ute.

My first car, a 1974 Falcon Ute, in the foreground, 1977.

Sitting on the bonnet of my second car, a Ford F100 Ute, c. 1980.

If they hadn’t sold ‘Ellengerah’, I would never have left. It was an exciting place to work, and I loved the buzz during shearing season. I met some real characters. When I returned to the Trangie Pub after a spell in Clermont, Queensland, I met a shearer whom I had first met on the train out to Trangie, and he was telling a story about a ‘Pommie jackeroo’. I asked him a few questions and worked out that it was my story that he had turned into a rather tall tale. I felt like a local legend in my own lifetime.

Ian Knight gave me a letter of recommendation to work at Frankfield station in Clermont, western Queensland, which was also owned by the Stanbroke Pastoral Company. I showed the letter to the manager, Mr Simms, who was a huge hulk of a man, but he wasn’t impressed by words. I had a wonderful variety of work at ‘Ellengerah’, but at Clermont, it was just cattle. Day in, day out. One day, I was in the corral when a bull charged at me and his two horns got lodged in the timber of the corral fence on either side of my hips. I was covered in white spume from his nose. The heavy bull had charged so fast that his horns had to be cut to free him from the fence. It was very scary, and I decided that I didn’t want to work with cattle anymore after this close encounter!

Frankfield Station, Clermont, Queensland, 1977.

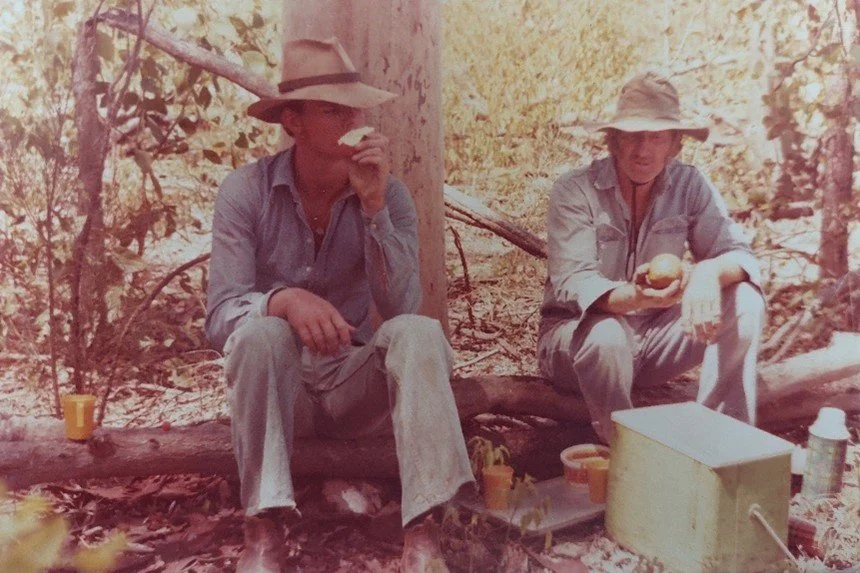

Allan (left) with my best friend Steve, having a ‘smoko’ on a pineapple farm near Yeppoon, Queensland, c. 1980.

I decided to take some holidays and took a road trip to Townsville. I met a guy called Steve and we got along so well that we decided to travel together. We picked fruit and vegetables on farms in Queensland but eventually ended up at Gundaline Station in the NSW Riverina. We worked 12-hour shifts and had to check that the irrigation pumps were working. Feral pigs, foxes and rabbits could destroy a crop, so the manager offered a bonus to anyone who shot feral animals. I don’t like guns, so I didn’t participate, but Steve decided to join in the hunt. Tragically, Steve was accidentally shot. He was my best friend. Out of respect for Steve, I took his body back to his hometown in Hamilton, New Zealand. His father blamed me for Steve’s death, but I think he was actually angry that he’d parted on bad terms with Steve, so he transferred his anger and regret to me.

When I returned to Australia, I was lost. I felt like I’d lost a brother. I didn’t want to go back to farming, so I started accepting other work, such as sapphire mining, gold prospecting and oil exploration. I worked for Santos at Ballera on the Jackson Oil fields on the western border of Queensland and New South Wales. Because I was a bit of a handyman by now, I was sent out to set up the camp. We were working in searing heat, but without the humidity that Brisbane gets. Our crew would fly out from Brisbane working three weeks on, and one week off each month. Usually, we flew out in twin propeller planes but one day we went out in a Learjet because several managers were visiting the site. Not many people can say that they travelled to work in a Learjet!

Allan prospecting for sapphires near Sapphire (west of Rockhampton), 1979.

Seismic oil exploration near Casino, NSW, c.1983. Allan is sitting on the tractor.

Allan and Bernadette at their wedding, 1983.

My dad never really adjusted to living in England and wanted to return to South America. My mother refused to go back there. After I came out with the BBM, my dad saw an opportunity and wrote to Australia House asking if they would support his application to immigrate and join his son. He was mostly retired but I think the woman who processed my application for the BBM took pity on him and endorsed his application. I was their guarantor. My younger sister came too. This was in 1981. By then, I’d bought ten acres of land at Jimboomba, south-west of Brisbane, and they joined us there.

I met my wife Bernadette (Bernie) through a friend, Frank Hatton, who had a Filipino wife, Fely. He was going to invite me over to dinner to meet Fely when we returned from our work in western Queensland. In the meantime, Bernadette was about to return to the Philippines after staying with her sister in Brisbane for almost a year. When she went to the Philippines Consulate in Brisbane to do some paperwork, they put her in touch with a woman who spoke the same dialect as Bernie and had recently arrived with no friends. That woman turned out to be Fely. Bernadette’s sister invited her and Frank over to dinner, and Frank invited me. We clicked. Bernie decided to cancel her plane ticket, and we started going out in 1982. We married at Mt Carmel Catholic Church in Coorparoo in 1983 and our two sons were also baptised there.

Allan and Bernadette with their sons John (right) and James, 1990.

In a way, Bernie also helped me to find my long-term career. I had to take her to the Emergency Department of the Mater Private Hospital in Brisbane one day and I noticed the wardsmen or orderlies working on the floor. I found out that you didn’t need any qualifications to do this work, so I put my name down with human resources and ended up working for Queensland Health for nearly 30 years. I worked in various hospitals in Brisbane, Toowoomba, Hobart and Logan City (south of Brisbane). There was plenty of variety. It gave me a secure job when my children were growing up and kept me out of the sun, thereby reducing my risk of developing skin cancer on my fair skin.

Bernie and I also worked together, running some takeaway food shops and renovating and landscaping the properties we bought. We worked hard in our adopted country. I came here with 40 pounds in my pocket, and I’ve been able to have a very comfortable life in Australia.

Australia could offer me a lifestyle that I couldn’t even dream of in the UK. It’s like winning the lottery if you can come to Australia. When I went back to the UK in 2009, I met up with a good friend from my childhood, and he’d only moved 500 metres up the road from where he grew up. I’d been to the other side of the world. I’ve never regretted coming to Australia, never.

Obviously, I miss certain things – like my boat, and the waterways around Norfolk; but whenever I leave this beautiful country, I just can’t wait to get my foot back on Australian soil.

We have six grandchildren and feel fortunate that we could raise our two sons in Australia. Our children grew up with a swimming pool and a tennis court and went to private schools. In the UK you’d have no hope of owning enough land to have those facilities if you didn’t go to university or have relatives in the right places. We’ve raised our boys to be independent and are proud of what they’ve achieved.

Without the BBM, Australia would only be a distant fantasy. I am grateful to Peter and Jean Foster who helped me get a job at ‘Ellengerah’. I want to take a trip back to Trangie to see if I can find Peter and also go to the Jackaroo Pub to see if the story about a ‘Pommie Jackaroo’ is still being told over the bar. I am very, very grateful to the BBM.

Allan and Bernadette Cain, 2025.